29 March 2006. A writes:

On the high hazard dams in NYC, Ridgewood Reservoir is empty, and has been

off line for years. Onassis Reservoir in Central Park is also no

longer a source. Silver Lake Reservoir is now just a lake, but there

is a reservoir underneath it (the largest underground water tank in

the world, I think.)

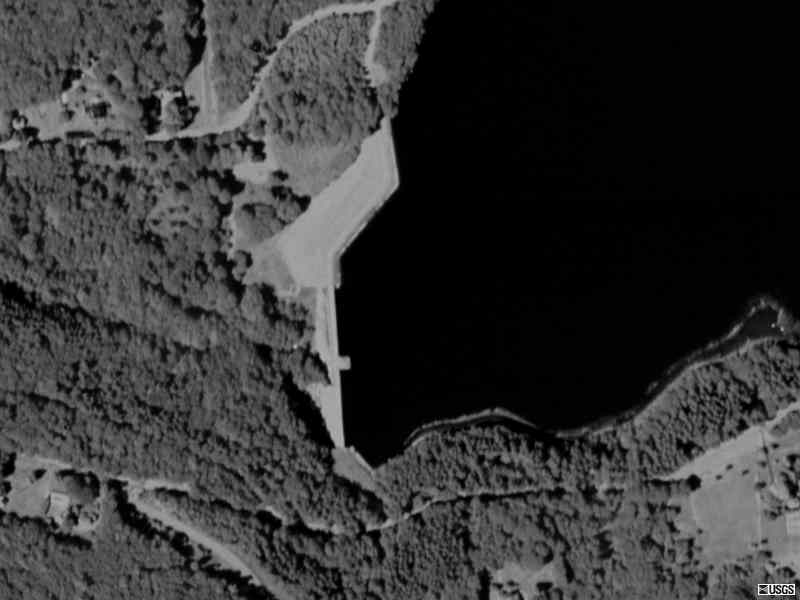

26 September 2003

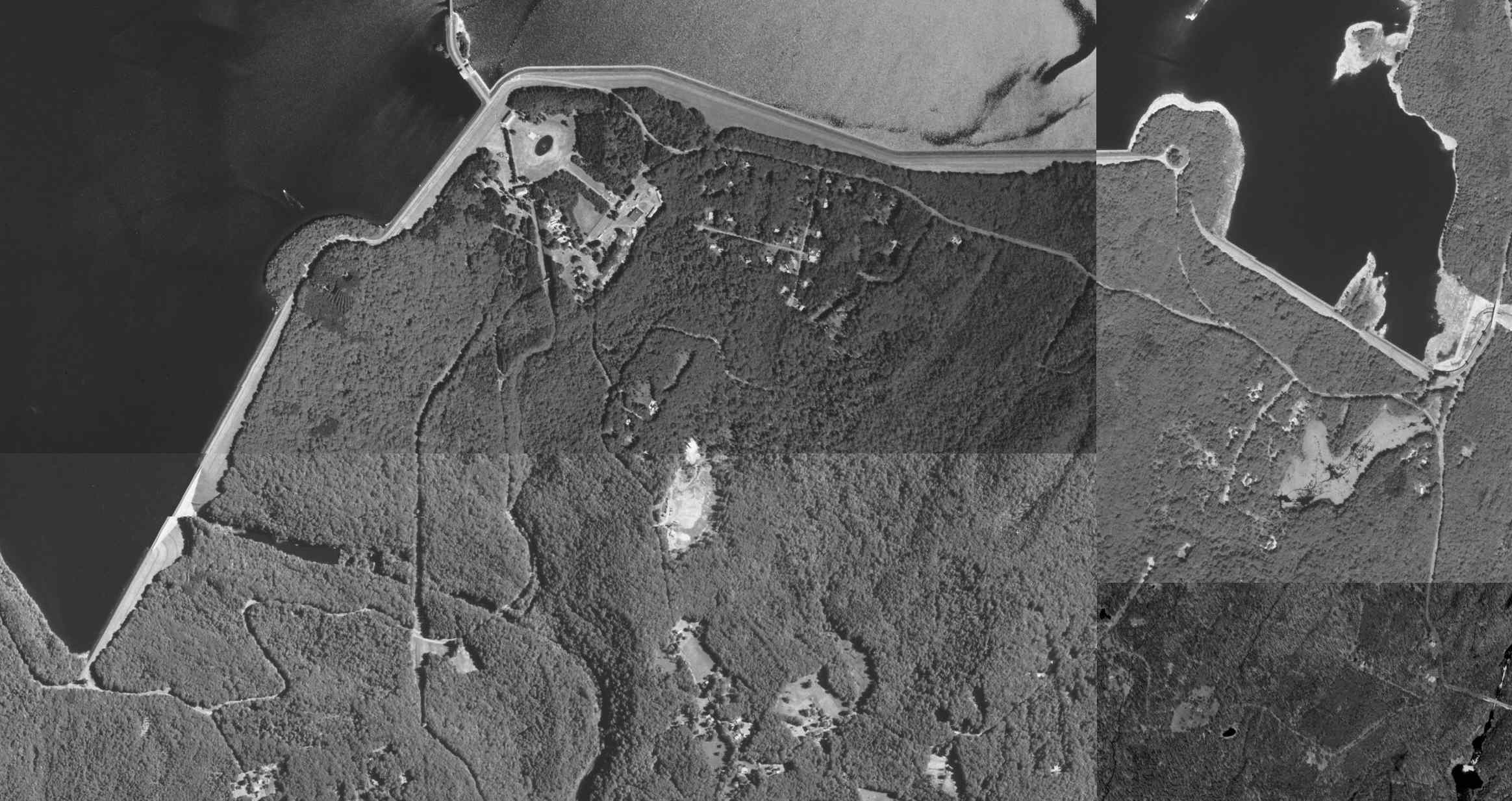

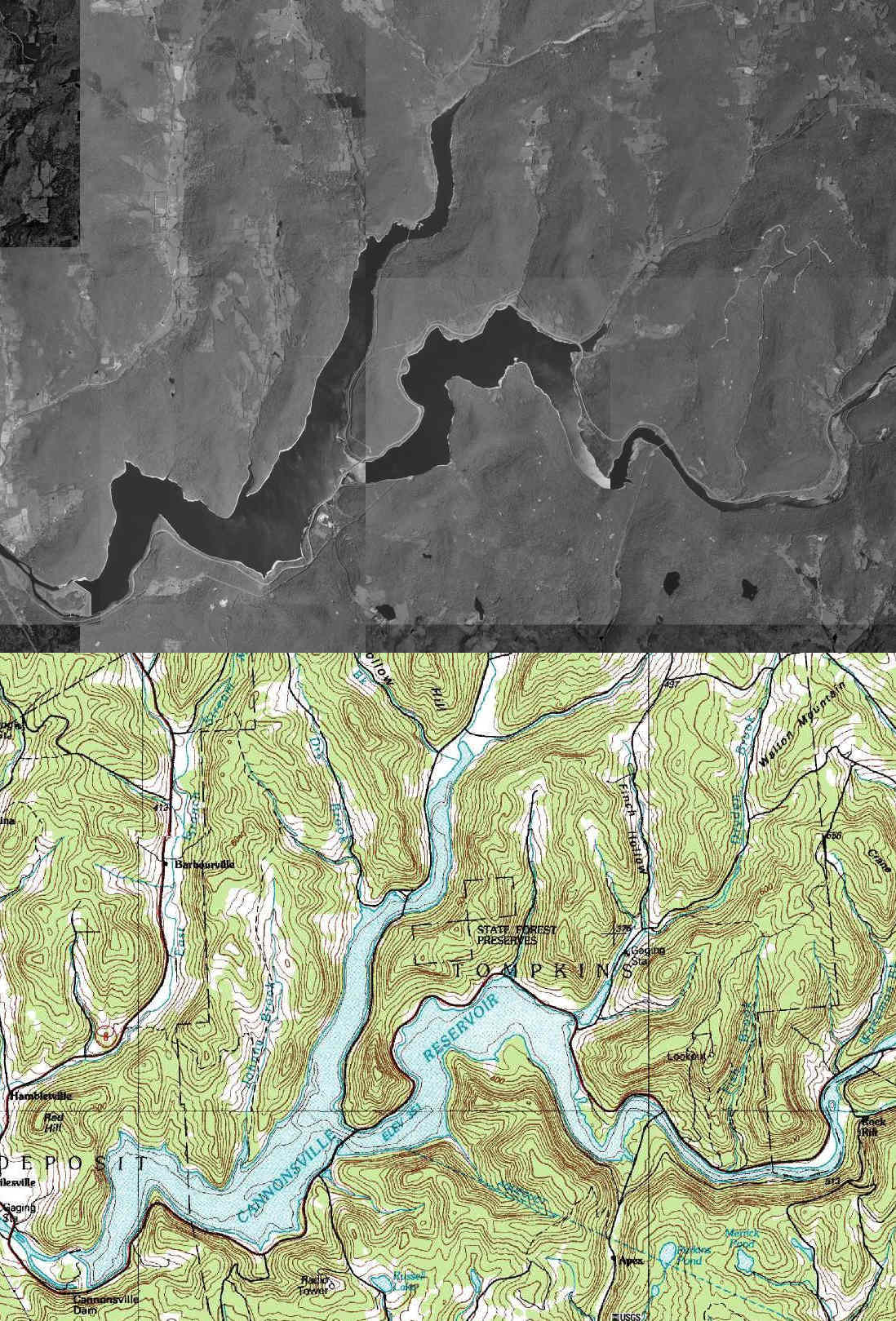

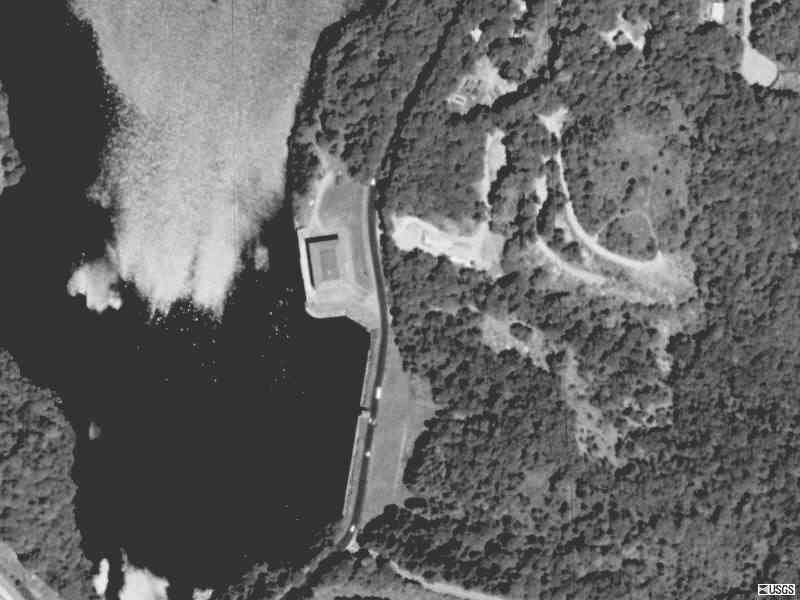

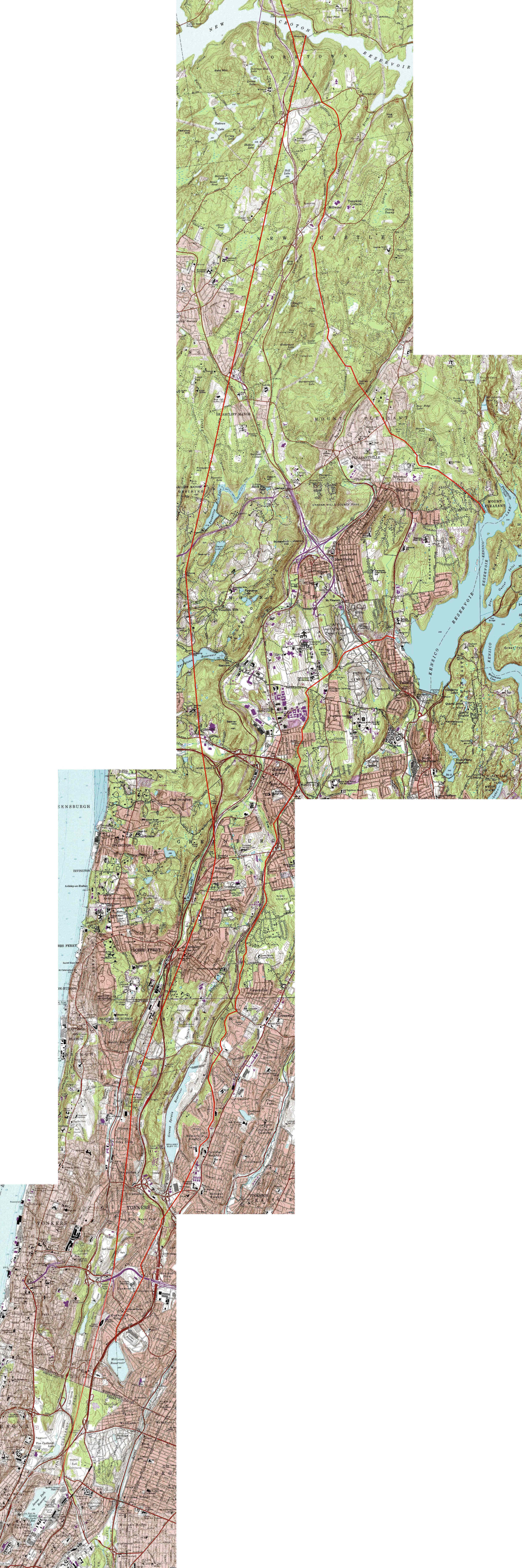

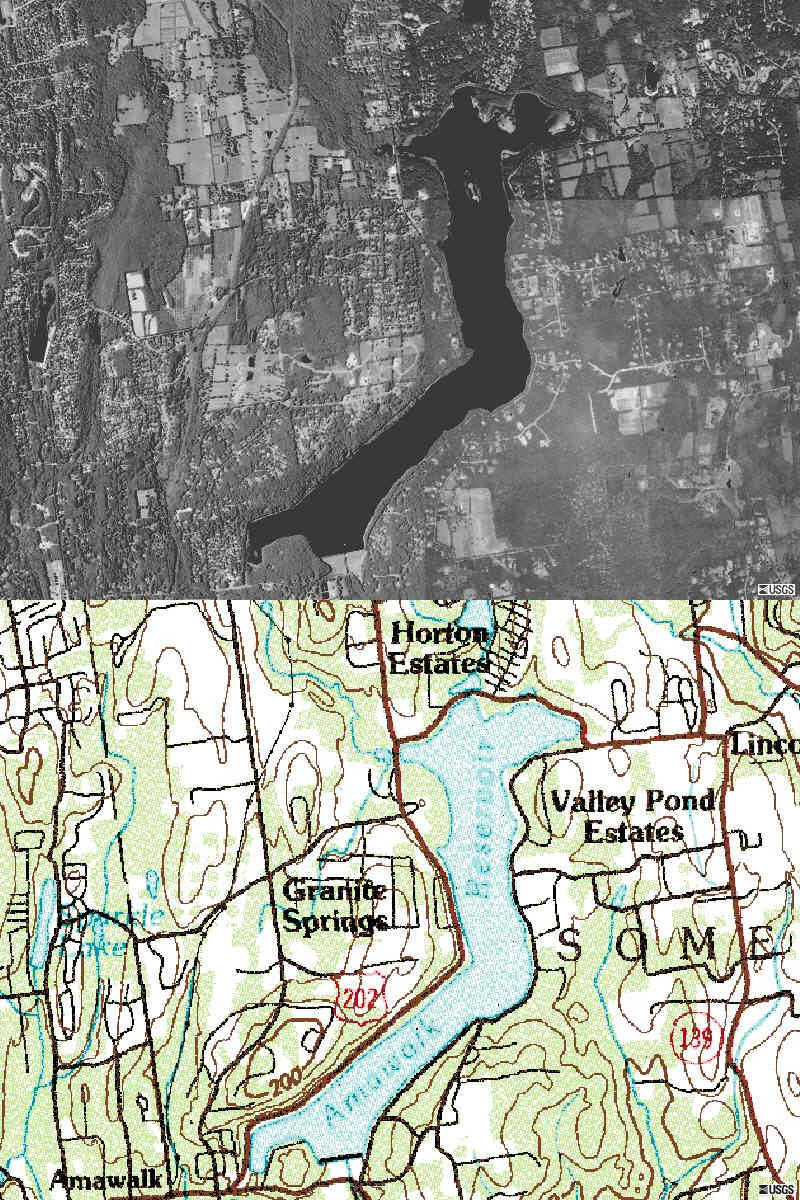

Source of aerail photos and topo maps:

Terraserver.

See related NYC high hazard dams:

http://cryptome.org/eyeball/nycd/nycd-eyeball.htm

"City of Water," David Grann, The New Yorker, September 1, 2003:

"Look," Ryan said, "if one of those tunnels goes, this city will be completely

shut down. In some places there won't be water for anything. Hospitals. Drinking.

Fires. It would make September 11th look like nothing."

Many experts worry that the old tunnel system could collapse all at once.

"Engineers will tell you if it fails it will not fail incrementally," said

Ward. "It will fail catastrophically." If City tunnel No. 1, which is considered

the most vulnerable, caved in, all of lower Manhattan and downtown Brooklyn,

as well as parts of the Bronx, would lose its water supply. If the aqueducts

gave out, the entire city would be cut off. "There would be no water," Ward

told me. "These fixes aren't a day or two. You're talking about two to three

years."

Mayor Michael Bloomberg recently noted at a press conference that "this city

would be brought to its knees if one of the aqueducts collapsed."

There is now the additional threat of terrorism. Although the public's attention

has focussed on the danger of someone poisoning the water supply, officials

believe that the system would likely dilute a toxin's effects. The greater

danger, they say, is that a terrorist might blow up one of the pipelines

before the third water tunnel is up and running. "That's the scary thing,"

Ward said. Fitzsimmons, the sandhogs' union leader said, "If you attacked

the right spots -- I hate to say this, but it's true -- you could take out

all of the water going into New York City."

Waterworks: a Photographic Journey through New York's Hidden Water

System, Stanley Greenberg, 2003. Greenberg writes:

I completed work on this project early in 2001. After September 11, it became

clear that neither I nor anyone else would be allowed to the access that

had been granted me for a long time. When I looked to publish this collection,

I encountered resistance from those who thought I was creating a handbook

for terrorists. Fortunately I found a publisher who believed, as I did, that

it is important to publish these pictures. we have to be very careful about

safeguarding our water supply, but we also have to stay connected to it.

We need to protect it from terrorists, but we need to protect it from farm

runoff, automobile pollution, acid rain, household sewage, and many other

forms of pollution that will only increase as development encroaches on the

watershed. Only by knowing our system will we be able to insure the quality

of our water.

See also Water for Gotham: A History, Gerard T. Koeppel, 2000.

http://www.epa.gov/region02/water/nycshed/supply.htm

New York City Water Supply

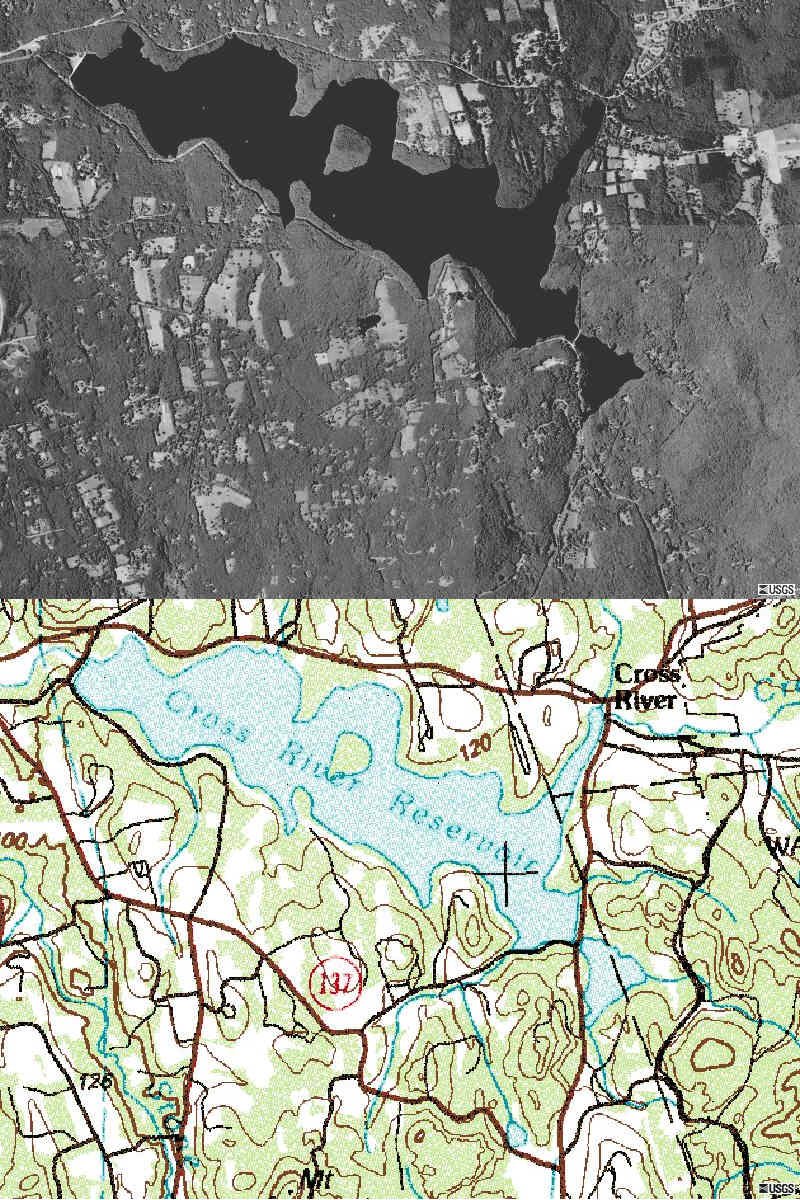

The New York City watershed covers an area of over 1,900 square miles in

the Catskill Mountains and the Hudson River Valley. The watershed is divided

into two reservoir systems: the Catskill/Delaware watershed located West

of the Hudson River and the Croton watershed, located East of the Hudson

River. Together, the reservoir systems deliver approximately 1.4 billion

gallons of water each day to nearly 9 million people in New York City, much

of Westchester County, and areas of Orange, Putnam, and Ulster Counties.

The Catskill Water Supply System, completed in 1927, and the Delaware Water

Supply System, completed in 1967 combine to provide about 90 percent of New

York's water supply. The combined Catskill/Delaware (Cat/Del) watersheds

cover 1,600 square miles. Water from the Catskill and Delaware systems is

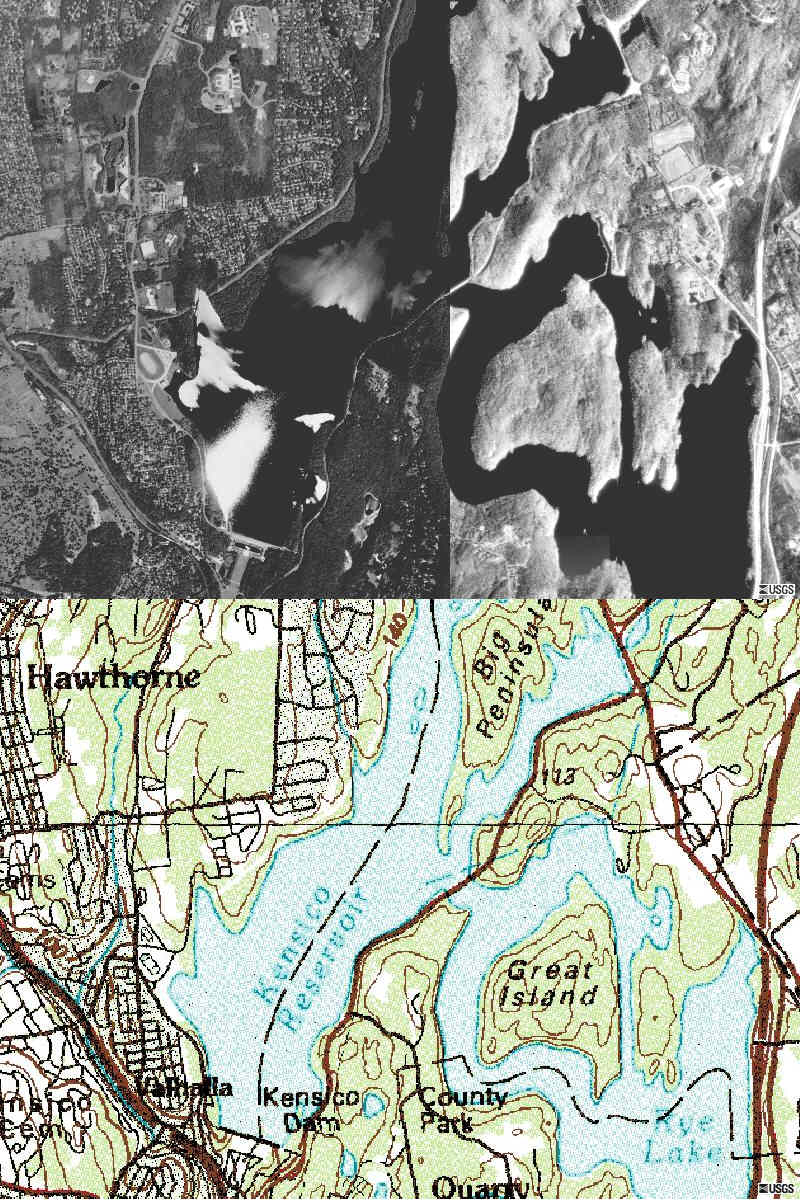

mixed in the Kensico reservoir before it is discharged into the Hillview

reservoir and on to the distribution system. Drinking water from the Cat/Del

System is of high quality and is currently delivered to New York consumers

unfiltered (in compliance with the Surface Water Treatment Rule).

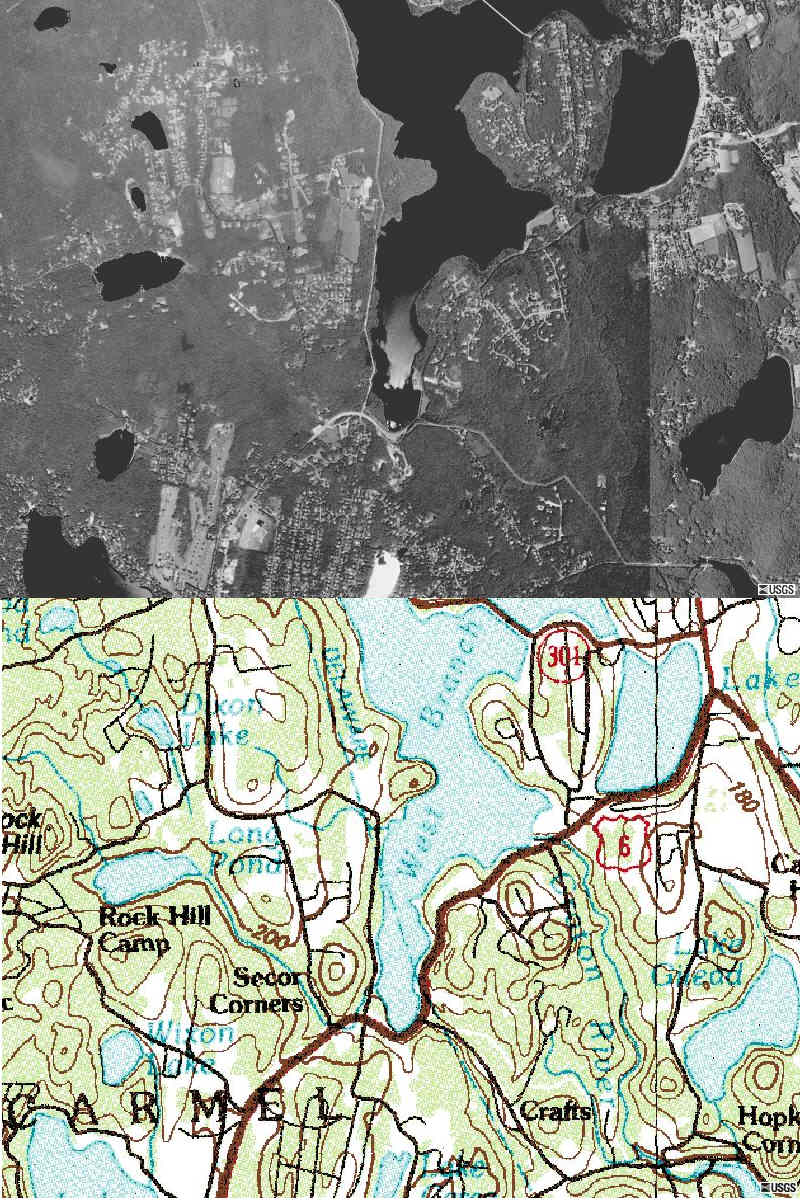

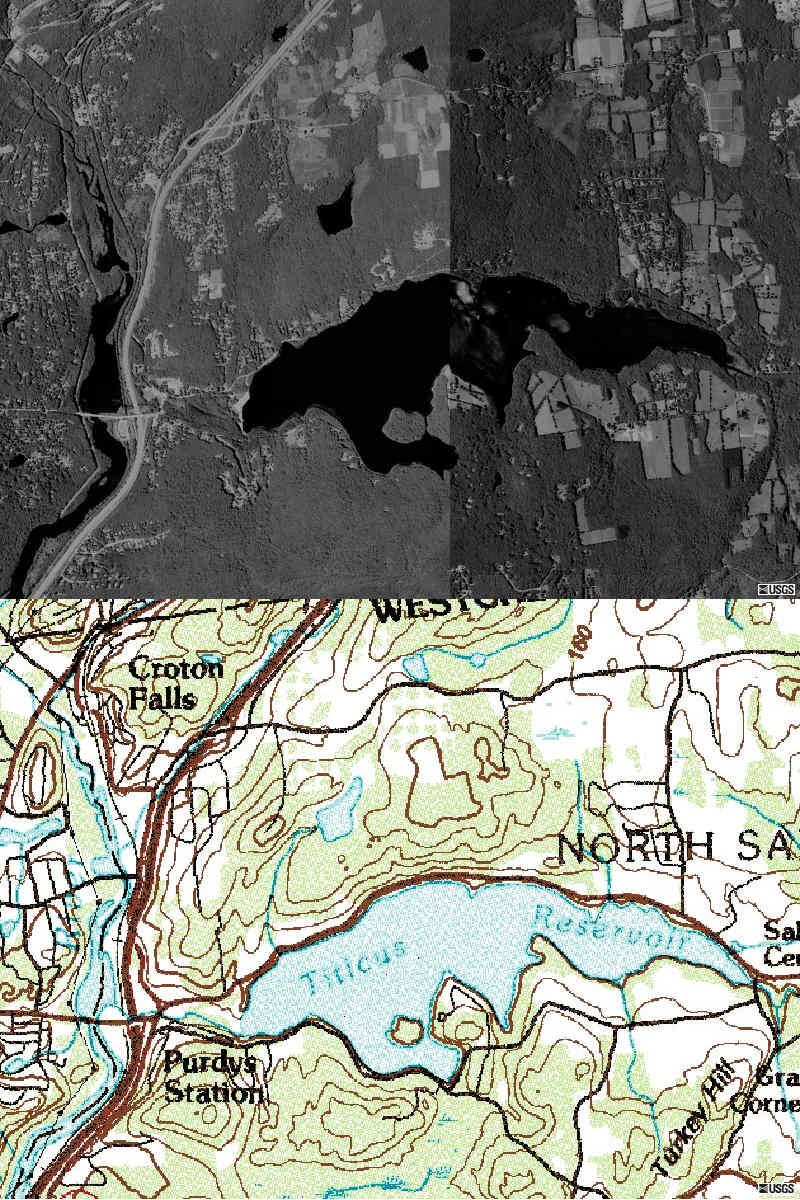

The Croton Water Supply System began service in 1842 and was completed prior

to World War I. Consisting of ten reservoirs and three controlled lakes,

the Croton system has the capacity to hold 95 billion gallons of water and

normally provides 10 percent of New York's daily water supply. The Croton

Watershed covers approximately 375 square miles East of the Hudson River

in Westchester, Putnam, and Dutchess Counties and a small section of Connecticut.

New York City Water Supply:

http://www.nyc.gov/html/dep/html/watersup.html

Source

http://www.nyc.gov/html/dep/html/history.html

History

Early Manhattan settlers obtained water for

domestic purposes from shallow privately-owned wells. In 1677 the first

public well was dug in front of the old fort at Bowling Green. In 1776, when

the population reached approximately 22,000, a reservoir was constructed

on the east side of Broadway between Pearl and White Streets. Water pumped

from wells sunk near the Collect Pond, east of the reservoir, and from the

pond itself, was distributed through hollow logs laid in the principal streets.

In 1800 the Manhattan Company (now The Chase Manhattan Bank, N.A.) sank a

well at Reade and Centre Streets, pumped water into reservoir on Chambers

Street and distributed it through wooden mains to a portion of the community.

In 1830 a tank for fire protection was constructed by the City at 13th Street

and Broadway as was filled from a well. The water was distributed through

12-inch cast iron pipes. As the population of the City increased, the well

water became polluted and supply was insufficient. The supply was supplemented

by cisterns and water drawn from a few springs in upper Manhattan.

After exploring alternatives for increasing supply, the City decided to impound

water from the Croton River, in what is now Westchester County, and to build

an aqueduct to carry water from the Old Croton Reservoir to the City. This

aqueduct, known today as the Old Croton Aqueduct, had a capacity of about

90 million gallons per day (mgd) and was placed in service in 1842. The

distribution reservoirs were located in Manhattan at 42nd Street (discontinued

in 1890) and in Central Park south of 86th Street (discontinued in 1925).

New reservoirs were constructed to increase supply: Boyds Corner in 1873

and Middle Branch in 1878. In 1883 a commission was formed to build a second

aqueduct from the Croton watershed as well as additional storage reservoirs.

This aqueduct, known as the New Croton Aqueduct, was under construction from

1885 to 1893 and was placed in service in 1890, while still under construction.

The present Water System was consolidated from the various water systems

in communities now consisting of the Boroughs of Manhattan, the Bronx, Brooklyn,

Queens and Staten Island.

Since 1842, there have been no significant interruptions of service other

than brief annual shutdowns for the purpose of routine inspections during

the period from 1842 to the Civil War.

In 1905 the Board of Water Supply was created by the State Legislature. After

careful study, the City decided to develop the Catskill region as an additional

water source. The Board of Water Supply proceeded to plan and construct

facilities to impound the waters of the Esopus Creek, one of the four watersheds

in the Catskills, and to deliver the water throughout the City. This project,

to develop what is known as the Catskill System, included the Ashokan Reservoir

and Catskill Aqueduct and was completed in 1915. It was subsequently turned

over to the City's Department of Water Supply, Gas and Electricity for operation

and maintenance. The remaining development of the Catskill System, involving

the construction of the Schoharie Reservoir and Shandaken Tunnel, was completed

in 1928.

In 1927 the Board of Water Supply submitted a plan to the Board of Estimate

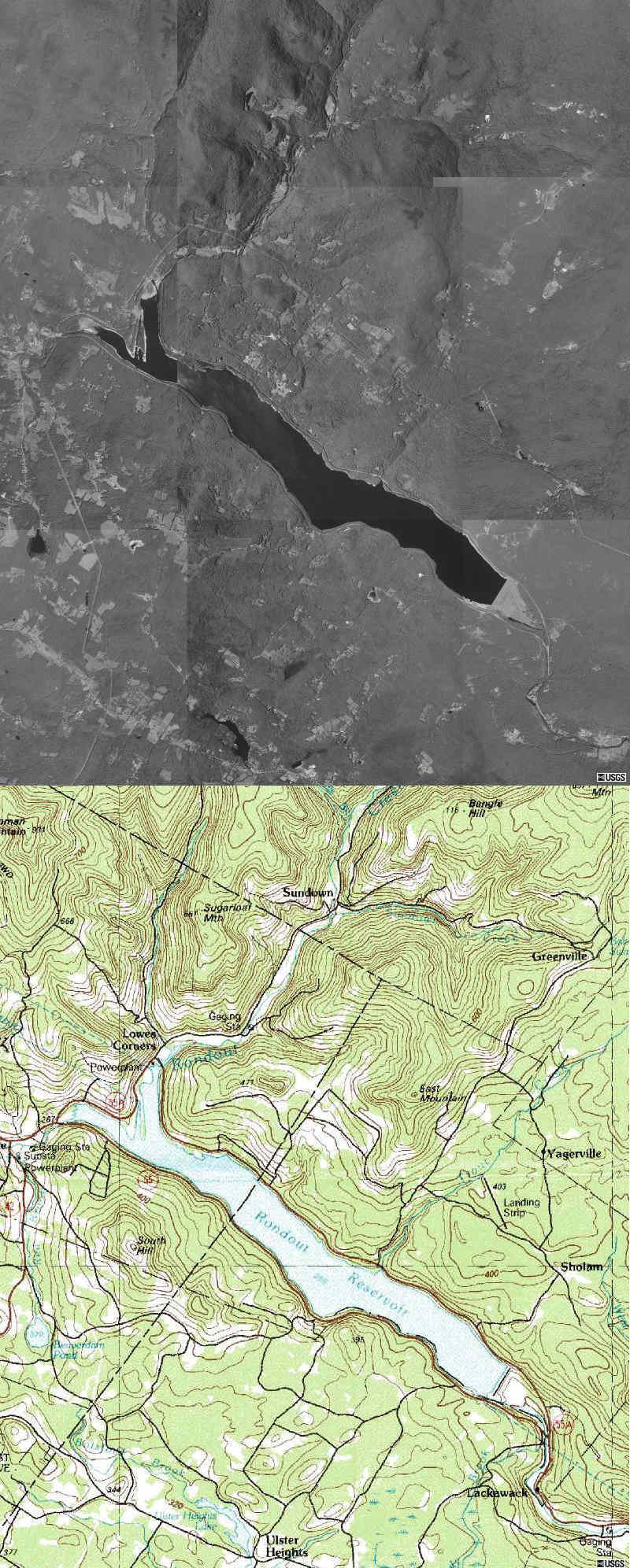

and Apportionment for the development of the upper portion of the Rondout

watershed and tributaries of the Delaware River within the State of New York.

This project was approved in 1928. Work was subsequently delayed by an action

brought by the State of New Jersey in the Supreme Court of the United States

to enjoin the City and State of New York from using the waters of any Delaware

River tributary. In May 1931 the Supreme Court of the United States upheld

the right of the City to augment its water supply from the headwaters of

the Delaware River. Construction of the Delaware System was begun in March

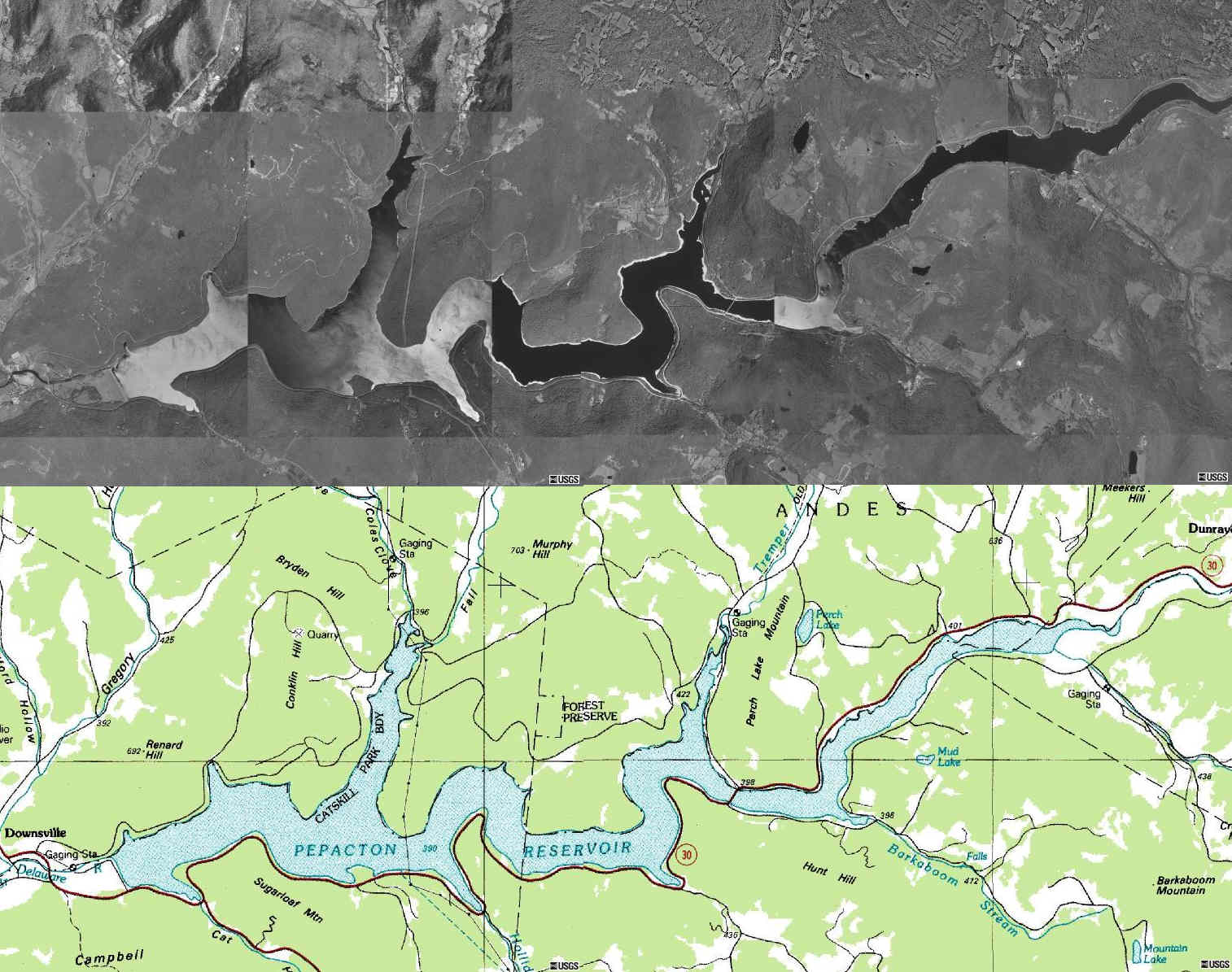

1937. The Delaware System was placed in service in stages: The Delaware Aqueduct

was completed in 1944, Rondout Reservoir in 1950, Neversink Reservoir in

1954, Pepacton Reservoir in 1955 and Cannonsville Reservoir in 1964.

Water for the system is impounded in three upstate reservoir systems which

include 19 reservoirs and three controlled lakes with a total storage capacity

of approximately 580 billion gallons. The three water collection systems

were designed and built with various interconnections to increase flexibility

by permitting exchange of water from one to another. This feature mitigates

localized droughts and takes advantage of excess water in any of the three

watersheds.

In comparison to other public water systems, the Water System is both economical

and flexible. Approximately 95% of the total water supply is delivered to

the consumer by gravity. Only about 5% of the water is regularly pumped to

maintain the desired pressure. As a result, operating costs are relatively

insensitive to fluctuations in the cost of power. When drought conditions

exist, additional pumping is required.

|